Entries Tagged 'NONFICTION' ↓

May 1st, 2009 — Books, Design, NONFICTION

Today’s edition of NONFICTION is, in part, a broadcast of a conversation on self-publishing with Ellen Lupton, director of the Graphic Design MFA program at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, and author of the new book, Indie Publishing: How to Design and Produce Your Own Book, a step-by-step guide to being your own publisher.

It should have aired last week, but, due to technical difficulties, didn’t. It’s a great talk, so I’m eager for you all to hear it. Hopefully, there’ll be no more boo-boos this time.

Tune in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

UPDATE: NONFICTION was pre-empted on Friday for a five-hor, “May Day special.” I was not made aware of this until I arrived at the station to do my show.

I’ll keep you abreast of when I air this, and other, programming.

April 28th, 2009 — Books, Film, NONFICTION

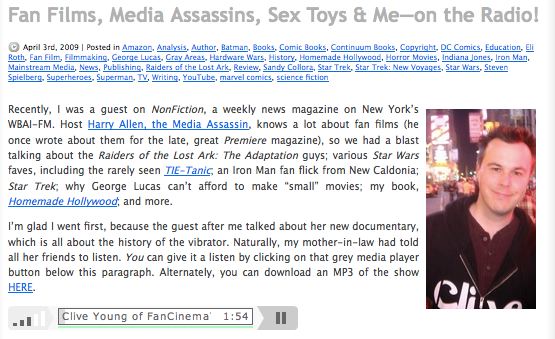

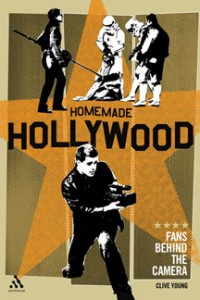

I hosted author Clive Young, below, on my WBAI radio show, NONFICTION, a few weeks ago, and covered him on MEDIA ASSASSIN, too. Clive recently wrote the book, Homemade Hollywood: Fans Behind The Camera, about amateur fan films: Movies made by ordinary people who love existing storylines about, and characters like, Batman, Spiderman, or Star Trek, and attempt to make their own versions of these films.

I’m really interested in this kind of cinema—I covered the Star Wars fan film phenomenon for the late, great PREMIERE magazine, back in 2001—and Clive has penned a thoughtful, thorough, accessible book. He’s got a great web site, too, one into which he clearly puts a lot of energy, and he mentioned his appearance on the NONFICTION, as you can see, above, complete with a link to the show. Thanks for the link amour, Clive. Keep the good work up.

April 24th, 2009 — Books, Design, Music, NONFICTION

The do-it-yourself movement in arts and crafts—accelerated by the wide availability of sophisticated digital technology, as well as access to information, and people, through the internet— is creating a boon in one very key area: Self-publishing. “Once referred to derisively as ‘vanity publishing,’ self-published books are finally taking their place alongside more accepted indie categories such as music, film, and theater.”

So says Ellen Lupton, director of the Graphic Design MFA program at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, and author of the new book, Indie Publishing: How to Design and Produce Your Own Book, a step-by-step guide to being your own publisher.

Ellen Lupton is a guest today on my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, April 24, at 2 pm ET.

As well, composer Jeff Snyder’s band, Scattershot, has remix credits with Public Enemy, among others, and they created and performed the opening and closing themes for NONFICTION. Today, he’s stopping by to discuss his latest passion: Inventing his own musical instruments. He’ll be showing and playing two of them, the Manta and the Countervielles.

You can hear Ellen Lupton and Jeff Snyder’s ideas—and Jeff’s music!—by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

April 17th, 2009 — Black Music, Books, Hip-Hop, NONFICTION

Fluid dynamics—the movement of particles in flow—remains one of the most intractable areas of study in all of science, with fluids in action being among the hardest phenomena to model, even with a very high-speed supercomputer.

The same may be true of hip-hop, if the relative absence of scholarly writing on the principles of the art form is any indication. Enormous swaths of text have been, and are being, composed on hip-hop’s master narrative: The Bronx, poverty, Kool Herc, Danceteria, Run-DMC, etc. Meanwhile, others delve into rap’s social and sexual politics, ad infinitum.

To my thinking, though, the real excitement truly, absolutely, lies near hip-hop’s epicenter, and its most elemental, fundamental questions; those corresponding to its mechanics.

For example, Why does rhyme work? Why does the act of mating like sounds grab a listener’s interest? I mean, when you think of it, why should so simple a trick hold the fascination of grown men and women, or anyone older than an infant?

Or, how do artists make word choices, winnowing away all possible semantics until they have crafted a narrative, or maybe a diatribe?

From what does rhythm derive its power? When a rapper speaks confidently over a strong meter, what new sound is he, by fusion, building, different from either his voice or the track, alone? Is this singing? If not, why not? How is doing this different from the way people made music before hip-hop’s advent?

And, most of all, when these and other queries are considered all together, how, and why, does hip-hop function as a system, one of both cognition and action?

Or, as Dr. Adam Bradley says in his amazing new text, Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop, in one of a seeming cluster of elegantly parsed, yet deeply thoughtful insights, “The MCs most basic challenge is this: When given a beat, what do you do?”

He continues:

“Rap is what results when MCs take the natural rhythms of everyday speech and reshape them to a beat. The drumbeat is rap’s heartbeat; its metronomic regularity gives rap its driving energy and inspires the lyricist’s creativity. ‘Music only needs a pulse,’ the RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan explains. ‘Even a hum, with a bass and snare—it’ll force a pulse, a beat. It makes order out of noise.’ Robert Frost put it even more plainly: ‘The beat of the heart seems to be basic in all making of poetry in all languages.’ In rap, whether delivered in English or Portugese, Korean or Farsi, we hear two and sometimes many more rhythms layered on top of one another. The central rhythmic relationship, though, is always between the beat and the voice. As the RZA explains, the beat should ‘inspire that feeling in an MC, that spark that makes him want to grab a mic and rip it.’

“Rappers have a word for what they do when the rhythm sparks them; they call it flow. Simply put, flow is an MC’s distinctive lyrical cadence, usually in relation to a beat. It is rhythm over time. In a compelling twist of etymology, the word rhythm is derived from the Greek rheo, meaning “flow.” Flow is where poetry and music communicate in a common language of rhythm. It relies on tempo, timing, and the consituitive elements of linguistic prosody: accent, pitch, timbre, and intonation.”

There are so many good things about writing like this: The clarity of Bradley’s language; the gentle way he uses technical terms, in order to bring readers into his secrets; the subtle manner by which he alludes to hip-hop’s global impact; his ear for pounding quotes; the good sense to mate RZA and Robert Frost, maybe for the first time, ever; the fact that all of this occurs within the book’s first six pages.

I had to make certain that Adam Bradley would be the guest, today, on my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, April 17, at 2 pm ET. And so he is.

You can hear his ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

April 10th, 2009 — Books, Children, Drugs, NONFICTION

A children’s book about pot sounds pretty much like a non-starter. So, when I found out that such a text existed, I absolutely had to see it, meet the author, and ask what on Earth had moved him to create such a reader.

What most struck me about Ricardo Cortés, author of It’s Just a Plant, was his willingness to have the discussion; his reasonable, non-combative air; and that apparently he’d completely thought through his entire argument, and was generally able to address each question I had.

That, and a definite modicum of courage. Even as a person who has never smoked or drank anything mind-altering, not even a Coca-Cola, I thought the idea of doing such a book brave, perhaps even necessary.

Mostly, though, as opposed to backing away from tough topics, I believe the fact that a subject is difficult makes a greater case for books on it, and that such treatises are the reason we have a 1st Amendment in the United States.

Since that conversation, I’ve had Cortés back to talk about his counter-terrorism coloring book, I Don’t Want to Blow You Up!, also published by his company, Magic Propaganda Mill. As well, It’s Just a Plant has been translated into other languages, including Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish, and, of course, Thai.

But you can revisit our meeting, as Ricardo Cortés is the guest today on this repeat edition of my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, April 10, at 2 pm ET.

You can hear this ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

March 27th, 2009 — Books, NONFICTION, Technology

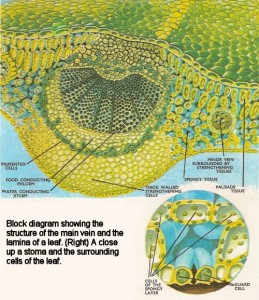

What do you see when you look at this picture?

Most would say they see a tranquil fall scene, perhaps somewhere in New England, and an empty road beckoning them to great times and even better memories. Of course, they’d be correct.

Few would say that they’re looking at an interface. When most people think of that word, they think of the stuff that you’re probably dealing with right now–clicking computer mouses, dragging cursors, scrolling bars, keyboards, the screen, etc.–all of which are tools that let you get to the motherboard, hard drive, CPU, and data that is “really” your computer.

But an interface is precisely what you’re seeing in the image. In fact, you’re seeing at least two: the forest, and then the road. Even more, depending on how you see the forest, and what you notice when you do, right, one could argue that you’re looking at, not just one but, a series of complex independent interfaces–ones that, together, we read as “nature”–all of them enabling access to a host of subsystems that trap moisture, scrub air, regulate and capture sunlight, house animals, fertilize soil, stabilize ambient temperature, ablate wind, feed users, etc., etc. Indeed, nature is continuously “computing.” It’s just so low-key about it that not only do we not notice, we don’t even think of it this way. (Plus, nature never crashes.)

But an interface is precisely what you’re seeing in the image. In fact, you’re seeing at least two: the forest, and then the road. Even more, depending on how you see the forest, and what you notice when you do, right, one could argue that you’re looking at, not just one but, a series of complex independent interfaces–ones that, together, we read as “nature”–all of them enabling access to a host of subsystems that trap moisture, scrub air, regulate and capture sunlight, house animals, fertilize soil, stabilize ambient temperature, ablate wind, feed users, etc., etc. Indeed, nature is continuously “computing.” It’s just so low-key about it that not only do we not notice, we don’t even think of it this way. (Plus, nature never crashes.)

What would it take to create hardware and software that do what nature’s do: Vanish, so that you don’t even perceive them any more?

In his book, Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing, author Adam Greenfield argues for a nearing era of “ubiquitous computing…a computing without computers, where information processing has diffused into everyday life, and virtually disappeared from view.”

Like Martin Luther, right, who wrought a revolution when he nailed his 95 theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, Greenfield has divided his text into 81 “‘theses on the next computing,’ divided into six sections.” As he says in the intro to his book,

Like Martin Luther, right, who wrought a revolution when he nailed his 95 theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, Greenfield has divided his text into 81 “‘theses on the next computing,’ divided into six sections.” As he says in the intro to his book,

This book is an attempt to describe the form computing will take in the next few years. Specifically, it’s about a vision of processing power so distributed throughout the environment that computers per se effectively disappear. It’s about the enormous consequences this disappearance has for the kinds of tasks computers are applied to, for the way we use them, and for what we understand them to be.

Although aspects of this vision have been called a variety of names – ubiquitous computing, pervasive computing, physical computing, tangible media, and so on – I think of each as a facet of one coherent paradigm of interaction that I call everyware.

How possible is this, or likely? Even more, what will it mean for human culture when our computers become so powerful that they just blend into the woodwork, so to speak?

Adam Greenfield is the guest today on this repeat edition of my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, March 27, at 2 pm ET.

You can hear his ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

March 20th, 2009 — DVD, Film, History, NONFICTION, Sex

“Relax yourself, girl / Please settle down….”

I may have finally cleared up for you what Q-Tip was actually saying (he told me himself) on the chorus of A Tribe Called Quest’s hit 1993 single, whose title I’ve also lifted for today’s post. But that track’s hook also summarizes the sentiment which drove the development of a medical implement that, today, is a common sexual aid: The vibrator.

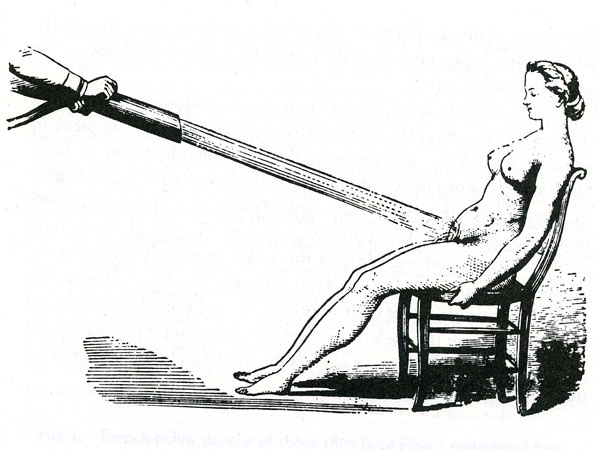

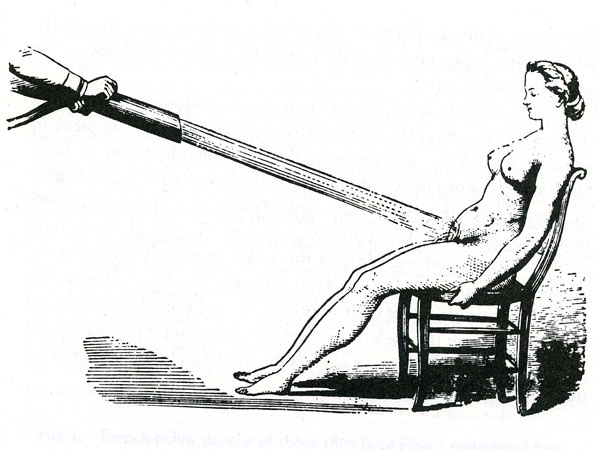

In the 19th century, doctors were commonly diagnosing “hysteria” in female patients, a condition marked, according to historian Rachel P. Maines, in her book, The Technology of Orgasm, as characterized by ”anxiety, sleeplessness, irritability,  nervousness, erotic fantasy, sensations of heaviness in the abdomen, lower pelvic edema and vaginal lubrication.” Hysteria was treated by inducing “paroxysm” in the patient, massaging her genitals until this state was reached. Manual methods, like the water massage technique, illustrated above, were applied. The development of early steam- or manually-powered vibrators, though, enabled doctors to stop using their hands and fingers for this task, while electric vibrators, such as this jackhammer-looking model, above right, made the process even more efficient.

nervousness, erotic fantasy, sensations of heaviness in the abdomen, lower pelvic edema and vaginal lubrication.” Hysteria was treated by inducing “paroxysm” in the patient, massaging her genitals until this state was reached. Manual methods, like the water massage technique, illustrated above, were applied. The development of early steam- or manually-powered vibrators, though, enabled doctors to stop using their hands and fingers for this task, while electric vibrators, such as this jackhammer-looking model, above right, made the process even more efficient.

If you’ve just read the previous paragraph in semi-disbelief, then said to yourself, “Hold up: In the 1800s, people were going to the doctor so he could get you off?”, you’re halfway there. Most people today would recognize “hysteria” as feminine sexual arousal. By categorizing it as an illness, however, Victorians avoided messy and uncomfortable discussions about the complexity of female sexuality and desire, relegating those discussions to the physician’s office, where they were, subsequently muted through categorization of the woman’s horniness as an illness. (There was no male equivalent of hysteria.) Argue producer/directors Wendy Slick and Emiko Omori, in their documentary PASSION & POWER: The Technology of Orgasm (a lot of title-borrowing today), hysteria “was a disease manufactured by doctors creating a lucrative clientele and a mutually camouflaged procedure that satisfied both” doctors and their patients.

Wendy Slick is a guest today on my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, March 20, at 2 pm ET.

But first, we’ll also talk with author Clive Young, whose new book, Homemade Hollywood: Fans Behind The Camera, right, traces another history: That of the so-called “Fan Film revolution—an underground movement where backyard filmmakers are breaking the law to create unauthorized movies starring Batman, James Bond, Captain Kirk, Harry Potter and other classic characters,” ones “which copyrights and common sense would never allow.” I wrote about Star Wars fan films for the much-lamented PREMIERE magazine, back in 2001, so I’m looking forward to the conversation.

But first, we’ll also talk with author Clive Young, whose new book, Homemade Hollywood: Fans Behind The Camera, right, traces another history: That of the so-called “Fan Film revolution—an underground movement where backyard filmmakers are breaking the law to create unauthorized movies starring Batman, James Bond, Captain Kirk, Harry Potter and other classic characters,” ones “which copyrights and common sense would never allow.” I wrote about Star Wars fan films for the much-lamented PREMIERE magazine, back in 2001, so I’m looking forward to the conversation.

You can hear Wendy Slick’s and Clive Young’s ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

March 13th, 2009 — Architecture, Books, NONFICTION

He created homes for such notables as the Vanderbilts, Pulitzers, and Whitneys, while overseeing the building of New York’s Pennsylvania Station, the Brooklyn Museum, and The American Academy in Rome. By doing so, architect Stanford White (1853 – 1906), of the firm of McKim, Mead, and White, became the 19th century’s most prominent designer of buildings, and the prototype for “starchitects” of today like Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas.

In our era, though, White is more often remembered for his indulgent lifestyle and scandalous end—he was shot in the face by the husband of a young dancer with whom White had been carrying on an affair—than for his often deeply sensuous and widely sourced works.

For this and certainly other reasons, Samuel G. White, a great-grandson of Stanford and also a practicing architect, is working to deepen history’s appreciation of his famed ancestor’s work. Not only was White recently called to restore a sumptuous Hudson River estate, above, built for the Astors by his great-grandfather, that had fallen into disrepair. As well, with his writer wife, Elizabeth, and architectural photographer Jonathan Wallen, White has produced Stanford White, Architect, a lush tome that, beyond documenting his forbear’s life and output, improves our understanding of both White’s insights and his legacy.

Samuel White is a guest today on my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, March 13, at 2 pm ET.

But, first, critic and curator Alastair Gordon takes a look at architecture 180˚ from White’s classically proportioned lines, focusing on the communes, crash pads, geodesic domes, and other folk structures of the Free Love era in Spaced Out: Radical Environments of the Psychedelic Sixties. In an era driven by altered consciousness, abandoning rules, returning to nature, and visualizing new social orders, living arrangements and spaces followed the spirit of the times, resulting in diverse and vital approaches to the built environment, ones perhaps little considered by historians, but nonetheless important and influential aspects of America’s architectural history.

You can hear Alastair Gordon’s and Samuel White’s ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

March 6th, 2009 — Architecture, NONFICTION, Photography

Husband-and-wife photography team James T. & Karla L. Murray give detailed, even affectionate, attention to the parts of New York City that most people merely dismiss as eyesores. In their earlier books, Broken Windows: Graffiti NYC and Burning New York, they recorded the craft of the aerosol artist, recording not only their masterworks but their words and intentions.

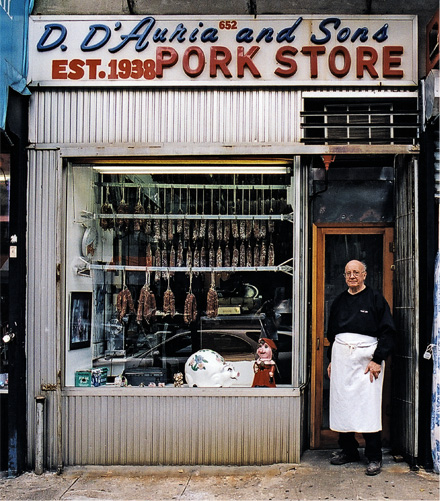

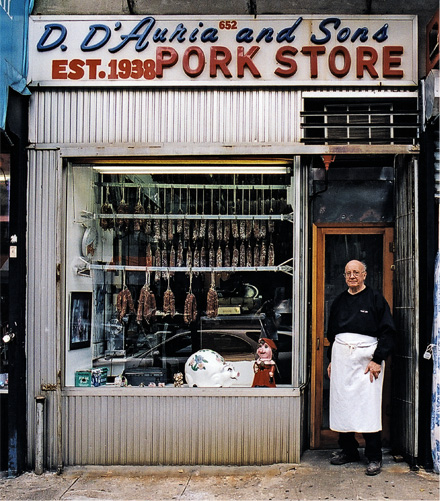

In their new volume, Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York, they document the most vulnerable structures in the urban landscape’s topography: The small, typically family-owned, street-level proprietorship. Historically, notes the web site, not only did these shopkeepers add life and vitality to, and in real ways bind together, these neighborhoods. As well, the corner stores served as economic stepping stones for “New York’s early immigrant population, a wild mix of Irish, Germans, Jews, Italians, Poles, Eastern Europeans and later Hispanics and Chinese.”

D. D’Auria and Sons Pork Store is a typical example. Founded in 1938, set in the Belmont section of the Bronx—that borough’s Little Italy—it closed in 2007, three years after the above photo was made. Subsequently, and in an ironic reordering of community priorities, a cell phone store replaced it. Then, says Karla, “that went out of business last year, and now the space is empty.”

Add to the mix whale-like box stores, gentrification, the skyrocketing cost of NYC real estate, and a host of other potent, seemingly random forces, and what you have in these small businesses, literally, is a dying way of life. Meanwhile, Jim and Karla Murray race to visually preserve the last of their spaces, using their “trusty old Canon 35mm film camera,” itself now a relic, to capture the look, character, color, and texture of the places where our great city was, in many senses, built.

Jim & Karla Murray are exhibiting selections from their Store Front photos at the Brooklyn Historical Society (128 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, NY; 718-222-4111) through March 29. As well, they’re guests today on NONFICTION, my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, this afternoon, Friday, March 6, at 2 pm ET.

You can hear this thoughtful and creative couple’s ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state area, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.

January 30th, 2009 — Medicine, NONFICTION, Science

Trembling at the toxic and terrifying sight, above?

Everybody knows what these two substances can do in combination with each other. That is, throw down a mouthful of Pop Rocks. Then, chase it with several gulps of soda. Wave goodbye to your family and your record collection, because your stomach is about to explode, killing you.

Really?

Andrea and Julia Ditkoff, 12 and 10, respectively, had a lot of questions like that one:

Why do you get a headache when you eat ice cream too quickly?

What’s that small, dewdrop-shaped thing in the back of your throat?

Why do people hiccup?

…not to mention the one that forms the title of their mother’s new book, Why Don’t Your Eyelashes Grow?: Curious Questions Kids Ask About the Human Body, by Dr. Beth Ann Ditkoff.

In fact, they came up with all the interrogatives Dr. Ditkoff uses in her text. She thought her daughters’ queries were, indeed, provocative, but commonplace. (That combining Pop Rocks and soda will kill you is a 30-year-old, urban myth.) Other children, and other adults, would want to hear the answers.

They will: Dr. Ditkoff is the guest today on my WBAI-NY / 99.5 FM radio show, NONFICTION, this afternoon, Friday, January 30, at 2 pm ET. We’ll be speaking with her, live, on the air, during the first half of the hour. Then, during the second half, we’ll take your calls over our master control studio line: (212) 209-2900.

You can listen to this thoughtful writer / physician’s ideas by tuning in at 2 pm. If you’re outside of the New York tri-state, check out our stream on the web. If you miss the live show, dig into our archives for up to 90 days after broadcast.