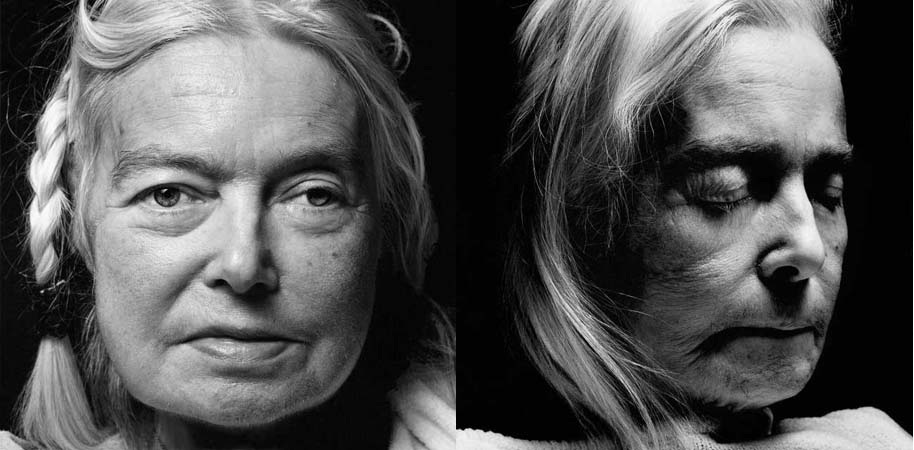

Edelgard Clavey, 67, December 5, 2003, then one month later

What is death?

Or, let me ask it this way: When, one moment, a person is alive, then, a moment later, they die, what has “happened,” or changed? Where have they, the person you knew and loved, “gone”? What is it that makes the difference between a person that you love and touch, and the shell you avert?

Questions of this sort inevitably course through one’s mind when contemplating German photographer Walter Schels’s and collaborator Beate Lakotta’s earthy, profoundly emotional portraits of terminally ill patients, before, and, their very first pictures, shortly after dying. (Thanks to very.fm for the heads up.)

The images were exhibited at the Wellcome Center in England from April 9 – May 18, but a collection of 22 images, plus interview and biographical text, representing the final days of eleven individuals, are on the Guardian‘s web site.

In an accompanying feature, the duo discuss the immense range of issues, personal and professional, that the work raised, both for them and their subjects. For example, Schels, 72, admits to

a crippling fear of death, and of dead bodies. “I was brought up in Munich during the war, and one day our house was bombed. I saw many bodies – limbs torn off, heads torn off, terrible things – and I have never forgotten them. Since that day, I was always afraid of dead bodies. Even when my mother died – she was 89 years old, and I’d taken her photograph earlier that very day – I didn’t want to see her after death.”

His fear was accentuated by his own advancing age, making it particularly difficult to photograph the bodies “between the relatives arriving and the undertaker coming,” said Lakotta, 42.

But, horrifying though photographing the bodies was, more shocking still for Schels and Lakotta was the sense of loneliness and isolation they discovered in their subjects during the before-death shoots. “Of course we got to know these people because we visited them in the hospices and we talked about our project, and they talked to us about their lives and about how they felt about dying,” explains Lakotta. “And what we realised was how alone they almost always were. They had friends and relatives, but those friends and relatives were increasingly distant from them because they were refusing to engage with the reality of the situation. So they’d come in and visit, but they’d talk about how their loved one would soon be feeling better, or how they’d be home soon, or how they’d be back at work in no time. And the dying people were saying to us that this made them feel not only isolated, but also hurt. They felt they were unconnected to the people they most wanted to feel close to, because these people refused to acknowledge the fact that they were dying, and that the end was near.”

Some of the subjects, says Schels, were bitter about how lonely the business of dying had made them feel – for some, this was why they agreed to take part in the project. “Some of the dying said, ‘It’s so good you’re doing this – it’s really important to show what it’s like. No one else is listening to me, no one wants to hear or know what it’s really like.'”

0 comments ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment