Is Gustavo Dudamel all that?

The Feb. 17 edition of 60 Minutes practically water-slided down the hunky, 27-year-old Venezuelan, and principal conductor of the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden. (He takes over as music director for the Los Angeles Philharmonic in September 2009.)

But is he really as great as they say he is?

I have absolutely no idea. From the looks of all the smart white people whose eyes light up when his name is uttered, I’m sure, to quote Lorraine Baines from Back to the Future, he’s an absolute dream.

I was fascinated by the fact—and this seems to be the default mode when talking about hot-to-trot, European classical music conductors—that the way they conveyed how talented he is is by how wildly and hard he shakes and swings his baton when conducting.

Is that all there is to it? I mean, there was one part in the 60 Minutes piece where, Dudamel, trying to express the way a particular musician should play a part, used the idea of softly, gently kissing a woman’s neck to make correct technique clear.

But, for the most part, whenever these TV newsmagazines want to tell you that there’s a hot new conductor, or pianist, or violinist, that’s gonna change the world, the fast ball always seems to be that “They’re craaazzzyyy, man!! Craaaazzzyyy!!!“, followed by some footage of the artist doing something bordering illegal with their instrument, or that, at least, we all have a common understanding is inappropriate.

So what? I mean, is this the best that great European classical music can do?

As may be obvious, this isn’t about Dudamel, right, as such. He seems like a warm, thoughtful, humble, and clearly gifted human being. I do have to admit, since this is a blog and not a piece for The New York Times, that I found the sight of his wife of two years, Eloisa Maturen, actually jarring. Her visibility gave the proceedings a bringing-sand-to-the-beach cast I couldn’t shake.

As may be obvious, this isn’t about Dudamel, right, as such. He seems like a warm, thoughtful, humble, and clearly gifted human being. I do have to admit, since this is a blog and not a piece for The New York Times, that I found the sight of his wife of two years, Eloisa Maturen, actually jarring. Her visibility gave the proceedings a bringing-sand-to-the-beach cast I couldn’t shake.

This has nothing at all to do with the lovely couple or the quality of their relationship, about which I know nothing. It has more to do with the view I’ve long had that young, powerful, male musicians in the classical genre, as in other ones, are, typically, satyrs, eager to screw anything that’s not already bolted to the floor. (Blair Tindall’s 2005 memoir, Mozart in the Jungle, on the incestuous NY classical scene of the ’70s and ’80s, is a robust reminiscence on the inner movements of said circle.)

Yet, in fact, this sexually-charged-image issue gets me nearer to the heart of what bothers me about the 60 Minutes piece. That is, we’re not fifteen seconds into the bit before Bob Simon is calling Dudamel “classical music’s newest rock star.” Of course, rock star is a commonly-used metaphor today; it’s a way to say that a person has become “the leading light” in a given field. But its irony, used here, should be clear to anyone who is following the classical scene. That is, does anyone use European classical music to say anything metaphorical to rock’s audience? (Beyond saying something is “a classic,” I mean.)

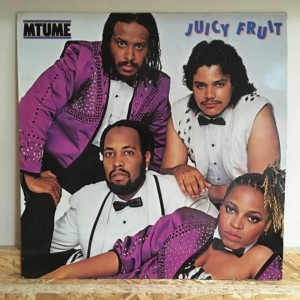

R&B legend James Mtume, right has uttered only two things I recall word-for-word: “You can lick me everywhere / Juicy fruit…,” and “The problem with classical music is that it suffers from technical exhaustion and aesthetic decay.” Do a Google search for the delimited expression “death of classical music.” I got back 10,800 hits. Trying “classical music is dead” got me 17,200. Whoa.

R&B legend James Mtume, right has uttered only two things I recall word-for-word: “You can lick me everywhere / Juicy fruit…,” and “The problem with classical music is that it suffers from technical exhaustion and aesthetic decay.” Do a Google search for the delimited expression “death of classical music.” I got back 10,800 hits. Trying “classical music is dead” got me 17,200. Whoa.

Everywhere you look, people are wondering what the future of the music will be. Orchestras are closing shop, unable to fill houses. Tindall has said that this is mostly due to symphony orchestra spending sprees local municipalities went on twenty and thirty years ago. However, it still doesn’t take away from the fact that phenomenally skilled instrumentalists are, today, often looking for any work they can get, like, to great effect, backing Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s music video.

In fact, to me, the most arresting sight in the 60 Minutes piece wasn’t the music’s barely concealed desperation for a hit conductor, but the reason for it: The half-empty Disney Hall you could barely see on the left hand of the screen, as Dudamel entered to guest-conduct at the end.

The future of the music, however, is actually very clear. It’s el Sistema, right (full name: The Fundación del Estado para el Sistema de Orquesta Juvenil e Infantil de Venezuela), which got some shine on 60 Minutes, but nowhere near what it truly deserved.

The future of the music, however, is actually very clear. It’s el Sistema, right (full name: The Fundación del Estado para el Sistema de Orquesta Juvenil e Infantil de Venezuela), which got some shine on 60 Minutes, but nowhere near what it truly deserved.

The program teaches children from poor Venezuelan neighborhoods how to play classical instruments, and has apparently been responsible for over a hundred youth orchestras sprouting up around the country.”The music saved me,” says Dudamel, a sistema graduate, in the 60 Minutes clip, and he gives back by going home and conducting the Simon Bolivar National Youth Orchestra.

On the link about El Sistema from Dudamel’s web site, I saw this text:

Lennar Acosta, now a clarinettist in the Caracas Youth Orchestra and a tutor at the Simón Bolívar Conservatory, had been arrested nine times for armed robbery and drug offences before the sistema offered him a clarinet.

“At first, I thought they were joking,” he recalls. “I thought nobody would trust a kid like me not to steal an instrument like that. But then I realized that they were not lending it to me. They were giving it to me. And it felt much better in my hands than a gun.”

I almost wanted to cry when I read those words. What a lovely, sublime paean to the redemptive power of music.

The text goes on to say that

Today, the sistema employs 15,000 music teachers. The government funds it to the tune of an annual $29 million – in a country where the average annual income is below $3,500….

Keep in mind that this is a government program; the government led by Hugo Chávez Frías, whom my government would love to see dead. (You’ll note that, despite the timeliness of the issue, Simon did not raise the subject of Chavez with Dudamel.)

When it comes right down to it, I think the problem I had with 60 Minutes is that the focus of the piece seems hopelessly turned inside out, as though looking through the wrong end of a telescope.

To them, Gustavo is great, because we’re drunk on celebrity, and, in some parts of the spacetime continuum, he is one. But, in fact, what’s really great is the sistema that produced him, and that made Lennar Acosta trade in his gun; something police forces struggle to do here.

They struggle because no one wants the toys and worthless trinkets they offer in pretend exchange. What people want are clarinets, and oboes. They want porches on which to gently play them in the summer’s evening light, in quintets composed of neighbors who also play because, come on, this is America, and here, everybody plays an instrument, and that’s what will ultimately save European classical, jazz, hip-hop, and the Constitution. They want the joy that comes, not only from playing their instruments, but from knowing that one lives in a country that will teach you how to use them well. It will do this, not for the disappearing market value of classical music—that is, to somehow restore the same—but because European classical music—like jazz, hip-hop, and the Constitution—is beautiful, and because it is great, and because that, simply put, is enough.

1 comment so far ↓

The System was started by Maestro Abreu and was given support by democratic governments even before Chávez’s name became a common household name. It is one of the few things in Venezuelan culture that Mr. Chávez has not destroyed. He has destroyed the Modern Art Museum, the Teresa Carreño Opera House. He uses this theater as a podium for his many \cadenas\. Abreu and Dudamel’s attitude regarding the political situation in Venezuela follow the premise of \see no evil, speak no evil\. Otherwise today, The System would be history. Reminds one of Nazi Germany.

Leave a Comment